Welsh Revival 1904–05

How the Holy Spirit Transformed a Nation

By Neil McBride, Founder and CEO of Downtown Angels

The Welsh Revival (1904–1905)

The Welsh Revival of 1904–1905 stands as one of the most remarkable and far-reaching religious movements in the modern history of Christianity. For just over a year, the small, predominantly rural nation of Wales underwent a profound spiritual awakening that transformed its churches, communities, and individual lives. What began as a quiet stirring in the hearts of a few devout believers quickly erupted into a nationwide movement of extraordinary religious fervour. Chapels that had once been sparsely attended were suddenly filled night after night. Entire communities stood a standstill as people flocked to prayer meetings, often abandoning their daily routines to seek spiritual renewal.

It is estimated that more than 100,000 people were converted to Christianity during this revival, a substantial number given Wales’s population. These conversions were not the result of mass marketing campaigns or organised evangelical efforts but rather a spontaneous and deeply emotional response to a palpable sense of divine presence. People were gripped with a deep awareness of their need for repentance, and a hunger for God swept through the valleys and towns. The revival was characterised by heartfelt prayer, passionate hymn singing, public confession of sins, and lives radically changed—sometimes overnight.

The effects of the revival rippled far beyond Welsh borders. News of the extraordinary events spread quickly through newspapers, missionary letters, and word of mouth, capturing the attention of Christian communities across Europe, North America, and beyond. Many were inspired to seek similar spiritual awakenings in their nations. The revival in Wales helped to ignite a global resurgence in evangelical fervour, influencing later movements such as the Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles, which played a foundational role in the rise of global Pentecostalism. The Welsh Revival stands not only as a defining moment in the spiritual life of Wales but as a pivotal chapter in the broader history of Christian revivalism worldwide.

Historical Context

At the turn of the 20th century, Wales underwent a significant transformation. The rapid pace of industrial growth—fueled by coal mining, steel production, and railways—had reshaped its people’s landscape and lives. Towns and cities expanded quickly, drawing thousands into hard labour in the mines and factories, often under harsh and exhausting conditions. Alongside this industrial development came a surge in cultural pride, marked by a renewed interest in the Welsh language, poetry, and music, including the renowned Eisteddfod festivals that celebrated national identity and artistic achievement.

Amid these changes, religion remained a dominant force in everyday life. Wales was often described as a “land of chapels,” where Nonconformist denominations, especially the Methodists, Baptists, and Congregationalists, held immense sway over communities’ moral and social fabric. These chapels were not merely places of worship but centres of education, political activism, and cultural expression. Sermons, hymn singing, and Sunday services were cornerstones of Welsh life, and most people professed Christian belief.

Yet beneath this religious structure, there were growing signs of spiritual stagnation. The vitality that had once characterized earlier revivals and religious movements in Wales appeared to wane. Many observed that church services had become formal and predictable, lacking the deep conviction and fervour of earlier generations. Spiritual lethargy and the moral challenges of urbanisation, economic inequality, and social unrest led many to conclude that the nation was drifting away from its spiritual roots. Alcohol abuse, gambling, and crime were reportedly on the rise in industrial centres, further evidence, to some, of a society in need of moral reawakening.

This growing concern created an atmosphere of expectation and yearning among clergy and laypeople alike. Ministers began to preach more earnestly on themes of repentance and revival, and prayer meetings multiplied as believers gathered to seek God’s intervention. There was a shared sense that a divine breakthrough was necessary and imminent. Some Christians had been praying fervently for years, believing that only a powerful move of the Holy Spirit could breathe new life into the churches and reach the people’s hearts once again.

It was in this spiritual climate of anticipation and longing that the Welsh Revival of 1904–1905 was born. It did not begin with any grand campaign or official denomination-wide initiative but rather as a spontaneous and fervent movement of the Spirit, ignited in small gatherings of sincere believers who dared to believe that God could once again stir their nation. What followed would exceed all expectations and leave a lasting imprint on Wales and the wider world.

The Spark: Evan Roberts

The central figure of the Welsh Revival was Evan Roberts, a 26-year-old former coal miner and theological student from Loughor, a small town near Swansea in South Wales. Born into a devout Christian family in 1878, Roberts was raised with a strong sense of spiritual discipline and an early sensitivity to the things of God. From his teenage years, he demonstrated a deep, almost consuming desire to seek the presence of God and was known for carrying his Bible with him to work underground in the mines. Despite his humble origins, he possessed a keen spiritual awareness and a powerful prayer life, often spending hours in solitude interceding for his community and his nation.

Roberts was not a charismatic public speaker in the traditional sense, nor did he seek fame or leadership. His passionate sincerity and unshakable belief that God was about to move extraordinarily set him apart. He had long prayed for revival and reportedly felt a profound spiritual burden for the lost, often weeping during prayer and pleading for souls. This intense spiritual hunger led him to attend a preparatory school for the ministry in Newcastle Emlyn. During this study period, Roberts experienced a life-changing encounter with God.

In October 1904, during a series of meetings and private devotions, Roberts experienced what he described as a baptism in the Holy Spirit. He later said that God had given him a vision of 100,000 souls being saved in Wales—a vision that burned so intensely within him that he felt compelled to return to his home in Loughor to begin preaching immediately. With the blessing of his instructors, Roberts left school and began organizing meetings at his home chapel, Moriah Chapel.

Roberts’ message was remarkably simple yet profoundly impactful: he urged people to confess their sins, set aside doubts, obey the prompting of the Holy Spirit, and surrender completely to God. His preaching was not marked by theological complexity but by a deep emotional resonance and a burning conviction that carried weight. Unlike many revivalists of the past, Roberts did not rely on structured sermons or orchestrated events. Instead, he was led by what he believed to be the direct guidance of the Holy Spirit.

As he travelled from town to town, often on foot or by train, news of the meetings spread like wildfire. Churches that invited him were quickly overwhelmed by the number of people who came; sometimes, entire congregations, families, and even villages would attend en masse. The meetings were spontaneous and fluid, often lasting for hours late into the night. Traditional preaching gave way to extended periods of prayer, emotional confession, powerful singing, and testimonies of transformation. There was an unmistakable sense that something beyond human planning was at work. People reported feeling convicted of sin merely by entering the building. Hardened sceptics broke down in tears, and communities once plagued by division and vice were brought to repentance.

There was no central organisation, revival committee, or formal plan; only a wave of spiritual intensity that seemed to move wherever Roberts and other revival leaders went. Roberts often stepped back during meetings, allowing others to pray, sing, or speak as they felt led. He believed fervently that the Holy Spirit was the true leader of the revival, and his willingness to yield control was one of the movement’s distinguishing features.

What had begun in a small chapel in a quiet village soon spread across Wales, capturing the entire nation’s attention and drawing thousands into a renewed relationship with God. Roberts’ obedience to the inner voice of the Spirit—despite his youth, lack of experience, and personal cost—made him a catalyst for one of the most extraordinary religious movements of the 20th century.

Characteristics of the Revival

Several distinctive features set the Welsh Revival of 1904–1905 apart from other religious movements of its time, contributing to its widespread appeal and profound impact on Welsh society. This was no ordinary religious gathering—it was a grassroots spiritual upheaval that touched every layer of life, from personal habits to public institutions.

-

Emphasis on the Holy Spirit

One of the most defining characteristics of the Welsh Revival was its intense emphasis on the direct work of the Holy Spirit. Attendees frequently described being overwhelmed by a tangible sense of God’s presence in the meetings, sometimes so powerful that people would fall to their knees in tears without a single word. There were countless reports of individuals being convicted of sin, experiencing healing, or being filled with spiritual joy simply by walking into a service. This overwhelming spiritual atmosphere often led to spontaneous prayer, singing, and repentance without formal preaching. The revival rejected rigid structure,e favouring Spirit-led spontaneity, creating gatherings that felt more like divine encounters than scheduled services.

-

Lay Participation

Unlike many traditional religious movements that depended on ordained clergy or prominent evangelists, the Welsh Revival was notably driven by laypeople. Ordinary men and women—many of them young, with no formal theological training—became the voices and vessels of the movement. People shared testimonies, prayed aloud, led hymns, and exhorted one another in faith. This democratisation of ministry gave the revival a fresh, raw, and authentic feel that broke down barriers between pulpit and pew.

The movement empowered everyday believers to participate actively in what they perceived as a sovereign move of God. Women, in particular, played significant roles in the revival, offering prayers, leading worship, and even preaching, which was highly unusual in the context of early 20th-century religious culture.

-

Emotional Worship

The revival meetings were marked by a deeply emotional and expressive form of worship, reflective of and amplified by Welsh cultural traditions. Congregations sang with fervour and unity, often without hymnbooks or musical instruments, relying instead on memory and shared spiritual passion. Traditional Welsh hymns like “Here is Love, Vast as the Ocean” became anthems of the revival. Songs would erupt spontaneously, and it was not uncommon for the entire assembly to sing in beautiful, harmonious unison for long periods, sometimes for hours. This emotional worship created a powerful collective experience and spiritual intimacy, drawing people in and fostering a deep sense of community and connection with God.

-

Social Transformation

The revival was not confined to the walls of chapels and churches; it spilt into the streets and workplaces, resulting in widespread moral and social transformation. Public houses and taverns reported dramatic drops in business, as habitual drinkers either turned away from alcohol or spent their evenings in revival meetings instead. Debts were repaid, stolen goods were returned, and long-standing feuds were reconciled. Even workplaces felt the impact—some coal miners, having undergone conversion, refused to use profanity, which reportedly confused the pit ponies that had become accustomed to being directed by coarse language.

Law enforcement officials in some towns and villages reported having almost nothing to do during the height of the revival. Crime rates plummeted so significantly that in several areas, magistrates and police officers were left idle. Rather than patrol the streets, some policemen formed quartets or choirs and joined the worship gatherings. It was said that jails were empty, and court sessions were cancelled for lack of cases. To many observers, these changes proved that the revival was not merely emotionalism but a profound moral and spiritual awakening that brought real societal change.

Spread and Impact

Though the Welsh Revival of 1904–1905 was geographically centred in Wales, its influence quickly transcended national boundaries and had profound international repercussions. In an age when mass communication was still in its infancy, it is remarkable how rapidly news of the revival spread. Reports of dramatic conversions, overflowing chapels, and transformed communities made their way into newspapers and periodicals, capturing the attention of readers within and beyond the British Isles. Personal letters, many written by eyewitnesses and participants, carried firsthand accounts of the revival’s intensity to friends, family members, and church leaders across Europe and North America. These vivid descriptions of spontaneous worship, public repentance, and divine encounters stirred deep interest and anticipation wherever they were read.

Missionaries, some of whom had returned to Wales on furlough, carried the revival’s fire back to mission fields worldwide. Others, still abroad, received letters describing what was unfolding at home and began to pray for similar movements in their own countries. As a result, the Spirit of revival began to leap across continents, sparking new awakenings in nations as diverse as India, Korea, South Africa, and Australia. The global evangelical community viewed the Welsh Revival as a localized phenomenon and a clear indication that God was moving freshly and powerfully worldwide.

In the United Kingdom, the revival’s energy extended into parts of England and Scotland, where churches experienced renewed vitality and prayer meetings multiplied. Young evangelists influenced by the Welsh movement carried the message to new cities and towns, often witnessing similar emotional responses and conversions.

One of the most significant international outcomes was the revival’s indirect influence on the Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles, which began in 1906. William J. Seymour, the African American preacher who led the Azusa Street mission, was deeply inspired by reports of what had happened in Wales. The emphasis on the Holy Spirit, spontaneous worship, and lay participation resonated strongly with the theological foundations of the burgeoning Pentecostal movement.

Though Seymour and his congregation were not directly connected to Evan Roberts or Welsh leaders, they saw the Welsh Revival as part of a larger wave of divine renewal sweeping across the globe. The Azusa Street Revival, in turn, became the catalyst for the modern Pentecostal and Charismatic movements, which today comprise hundreds of millions of believers worldwide.

The Welsh Revival thus occupies a central place in the chain of spiritual awakenings that helped shape modern evangelical Christianity. Its message, methods, and impact travelled far beyond the chapels of Wales, influencing the course of global Christianity in the 20th century and beyond. From remote mission outposts to bustling urban centres, people prayed for and experienced similar outpourings of the Holy Spirit, many of which traced their inspiration and faith back to the fires that first burned in the hills and valleys of Wales.

Conclusion

The Welsh Revival of 1904–1905 was far more than a series of emotionally charged church meetings; it was a national spiritual awakening that dramatically reshaped Wales’s religious, social, and cultural fabric, leaving an enduring legacy on the global Christian landscape. At a time when spiritual apathy and social unrest seemed to be rising, the revival emerged as a divine interruption —a moment in history when ordinary people encountered an extraordinary move of God. Its effects reached far beyond chapel walls, permeating schools, workplaces, streets, and homes and touching nearly every sector of society. In a matter of months, it transformed the collective spiritual consciousness of a nation.

What made the revival truly remarkable was not merely the number of conversions—though more than 100,000 people were reportedly brought to faith—but the depth of transformation it produced. This movement was not driven by human strategy or institutional agendas but by fervent prayer, deep repentance, and the active leading of the Holy Spirit. The revival had no celebrity preachers, large-scale advertising campaigns, or formal structure. Instead, it was fueled by humble, Spirit-filled believers, many of whom were young and previously unknown, who responded to a divine calling and stepped forward in faith.

One of the most compelling aspects of the Welsh Revival was its organic and participatory nature. Services often unfolded spontaneously, with individuals rising to confess sins, sing hymns, or offer heartfelt prayers. The absence of formal preaching or liturgy made space for the congregation to become co-creators in the worship experience, and it was this Spirit of openness and authenticity that drew many to the movement. Above all, the revival was marked by a palpable sense of God’s presence—a sacred atmosphere that convicted hearts, healed wounds, and ignited a passion for holiness and spiritual renewal.

Although the revival’s visible intensity waned after 1905, its legacy endured, not only in the lives that were changed in Wales but also in the wave of revivals it helped inspire worldwide. Its influence contributed to the birth of the Pentecostal movement, stirred fresh zeal among missionaries, and encouraged countless pastors and believers to seek similar outpourings in their communities. Today, the Welsh Revival is a timeless testimony to what can happen when people set aside distractions and wholeheartedly pursue a deeper encounter with God.

In an age increasingly marked by disconnection, secularism, and spiritual searching, the story of the Welsh Revival remains a powerful and enduring resonance. It reminds the modern church that revival does not begin in grand cathedrals or with eloquent speeches but in the quiet prayers of the faithful, the humility of the heart, and the willingness to be led by the Spirit. It remains a powerful and enduring example of how God can use ordinary people in extraordinary ways to awaken a nation—and, through it, touch the world.

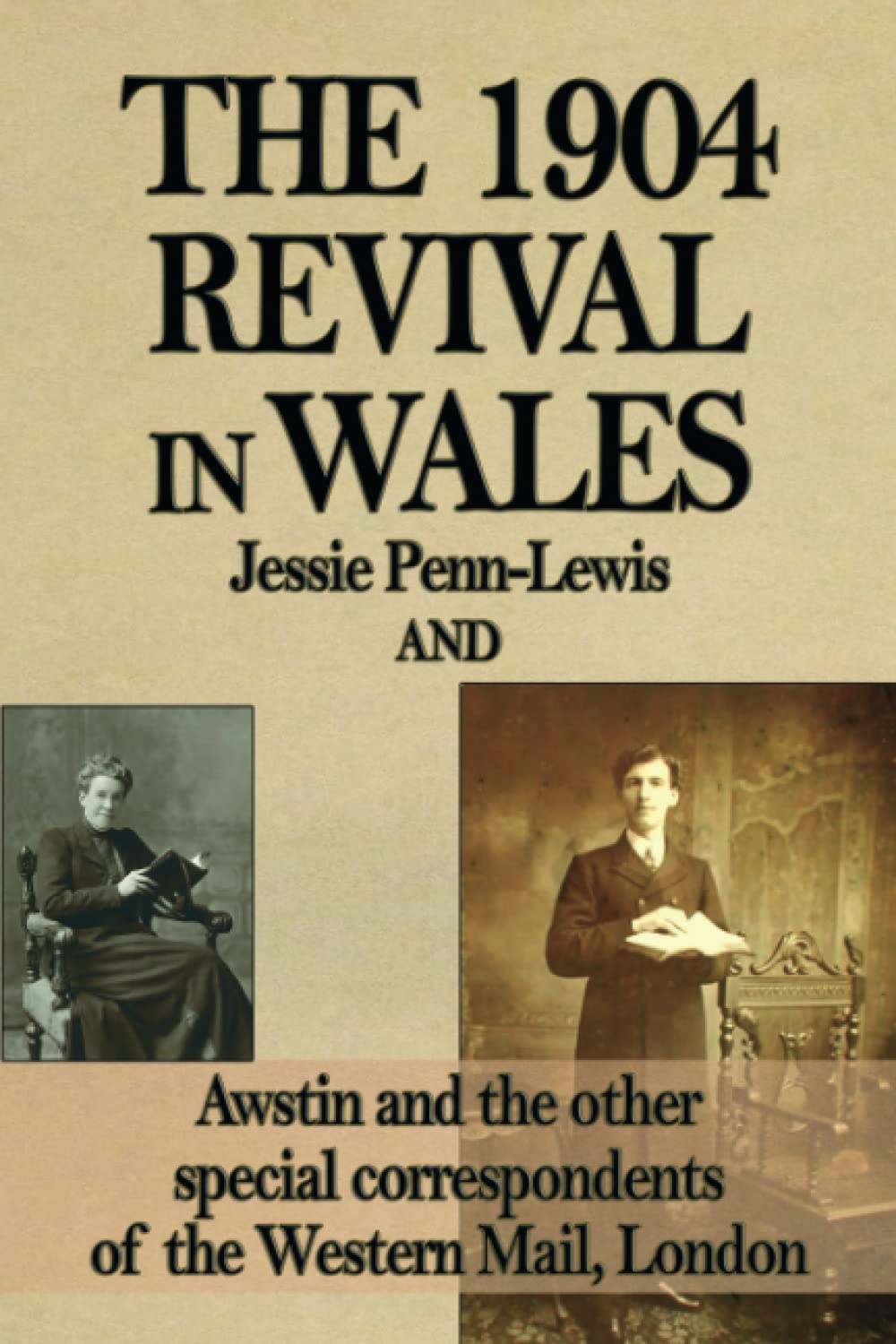

The 1904 Revival in Wales

Jessie Penn-Lewis

Downtown Angels, summary:

The 1904 Revival in Wales is a compelling two-in-one volume that offers firsthand accounts of the Welsh Revival, a profound spiritual awakening that swept across Wales in 1904–1905. The first part, The Awakening in Wales and Some of Its Hidden Springs, is authored by Jessie Penn-Lewis, a Welsh evangelist and close associate of Evan Roberts, one of the revival’s central figures. Penn-Lewis provides a detailed narrative of the revival’s events, emphasising the central role of the cross of Christ in this divine visitation. The second part, ‘The Religious Revival in Wales 1904,’ is penned by Austin and other special correspondents of the Western Mail, London. This section offers journalistic insights into the revival, capturing public response and the movement’s widespread impact.

Together, these accounts provide a multifaceted perspective on the Welsh Revival, blending personal testimony with journalistic observation. The book is available in various formats, including paperback and eBook, making it accessible to a wide audience interested in revival history and spiritual awakenings. For those seeking a deeper understanding of this significant event in Christian history, The 1904 Revival in Wales serves as an invaluable resource.

Please click on the link: https://amzn.to/449xT8u.

Sounds from Heaven

Colin and Mary Peckham

Downtown Angels, summary:

Sounds from Heaven by Colin and Mary Peckham offers a compelling account of the 1949–1952 revival on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland. This 288-page volume combines historical context, biographical insights, and firsthand testimonies to depict a profound spiritual awakening that transformed a remote island community. The book includes reports from Duncan Campbell, the revival’s key figure, and personal narratives from individuals like Mary Peckham, who was converted during the revival. Their stories provide a vivid picture of the revival’s impact on individuals and communities.

Critics and readers alike have praised Sounds from Heaven for its heartfelt storytelling and spiritual depth. Brian H. Edwards, a theologian and author, described it as “stirring stuff” that captures the atmosphere of an island overwhelmed by the Spirit of God. The book’s blend of historical narrative and personal testimony makes it a valuable resource for those interested in revival history and the workings of the Holy Spirit in communities. Its enduring popularity underscores its significance in Christian literature on revival.

Please click on the link: https://amzn.to/4pkLZwe

To continue reading more uplifting articles from Downtown Angels, click the image below.

Evan Roberts

The Extraordinary Welsh Evangelist Behind the 1904–1905 Revival

Evan Roberts was a humble coal miner whose deep passion for God sparked one of the most remarkable spiritual awakenings in modern history—the Welsh Revival of 1904–1905. Through prayer, preaching, and an unwavering commitment to holiness, Roberts inspired thousands to turn to God in repentance and faith. Communities were transformed, churches overflowed, and countless lives were renewed as God’s Spirit moved powerfully across Wales, leaving a legacy of revival that continues to inspire today.

Roberts’ life reminds us that God can use ordinary people to achieve extraordinary purposes when hearts are fully surrendered. His story encourages believers to seek God earnestly, pray boldly, and trust that the Spirit can ignite change beyond imagination. If you’re captivated by powerful accounts of revival and the work of the Holy Spirit, click the image below to continue exploring the life and ministry of Evan Roberts.